In late April, a slow-moving storm over Texas and Oklahoma spawned an outbreak of 39 tornadoes. That event was just a fraction of the more than 400 tornadoes reported that month, the highest monthly count in 10 years. And the storms kept coming.

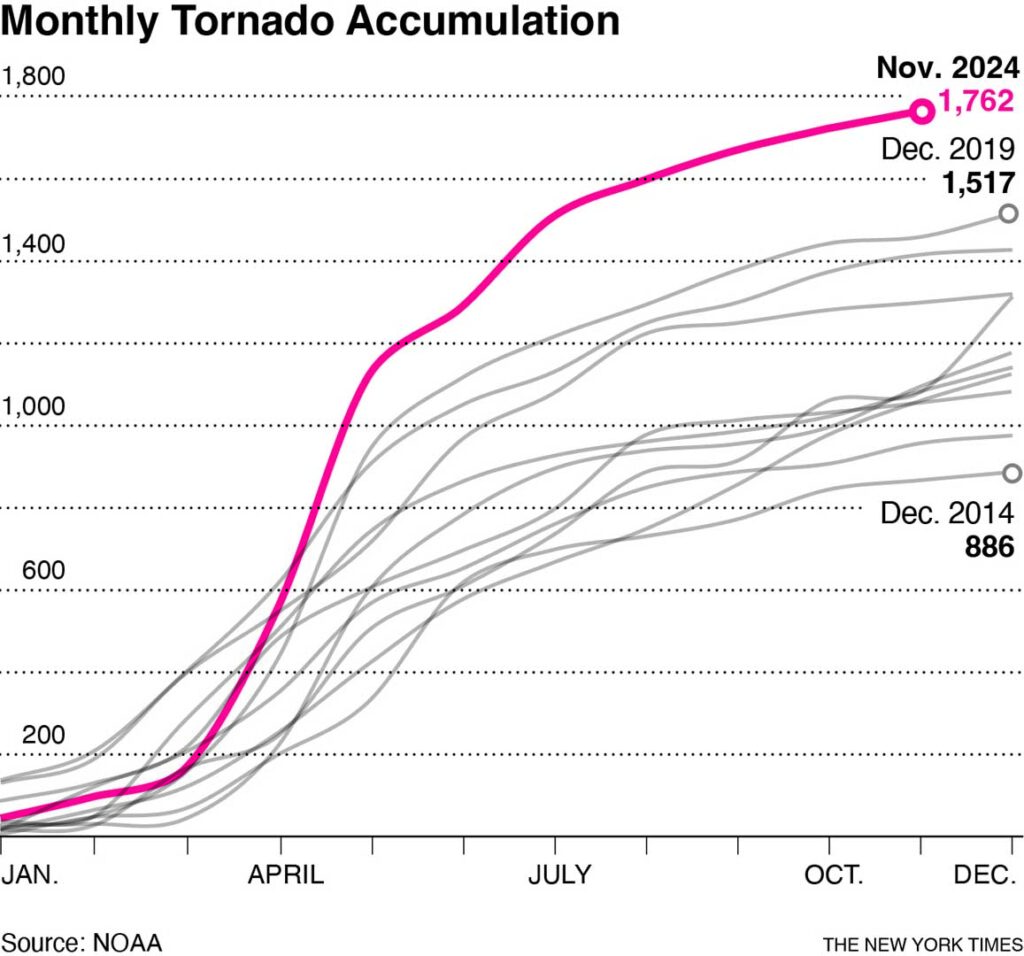

Through November, more than 1,700 tornadoes were reported nationwide, preliminary data shows. At least 53 people had been killed across 17 states.

Not only were more tornadoes reported, but 2024 was also on track to be one of the costliest years ever in terms of damage caused by severe storms, according to the National Center for Environmental Information. Severe weather and four tornado outbreaks from April to May in the central and southern United States alone cost $14 billion.

We will not know the final count of 2024’s tornadoes until 2025 — the data through November does not yet include tornadoes like the deadly one that touched down Saturday in southeastern Texas. That’s because confirming and categorizing a tornado takes time.

After each reported event, researchers investigate the damage to classify the tornado strength based on 28 indicators, such as the characteristics of the affected buildings and trees. Researchers rate tornadoes using the Enhanced Fujita scale (EF) from 0 to 5.

But 2024 could end with not only the most tornadoes in the last decade, but also one of the highest counts since data collection began in 1950. Researchers suggest that the increase may be linked to climate change, although tornadoes are influenced by many factors, so different patterns cannot be attributed to a single cause.

44 Miles of Destruction

In May, a mobile radar vehicle operated by researchers from the University of Illinois measured winds ranging 309 to 318 mph in a subvortex of a tornado on the outskirts of Greenfield, Iowa.

The event, an EF4, was among the strongest ever recorded. NASA tracked the line of destruction of the tornado over 44 miles.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimated the damage caused by the Greenfield tornado, which killed five people and injured dozens more, at $31 million.

While most tornadoes this year were not as deadly or destructive, there were at least three more EF4 storms, described by NOAA as devastating events with winds ranging from 166 to 200 mph. These violent tornadoes caused severe damage in Elkhorn-Blair, Nebraska, and in Love and Osage counties in Oklahoma.

While losses from tornadoes occur every year, extreme events such as hurricanes can also produce tornadoes with great destructive capacity. In October, more than 40 tornadoes were reported in Florida during Hurricane Milton, three of them rated EF3. According to the Southeast Regional Climate Center, EF3 tornadoes spawned by hurricanes had not occurred in Florida since 1972.

A Vulnerable Region

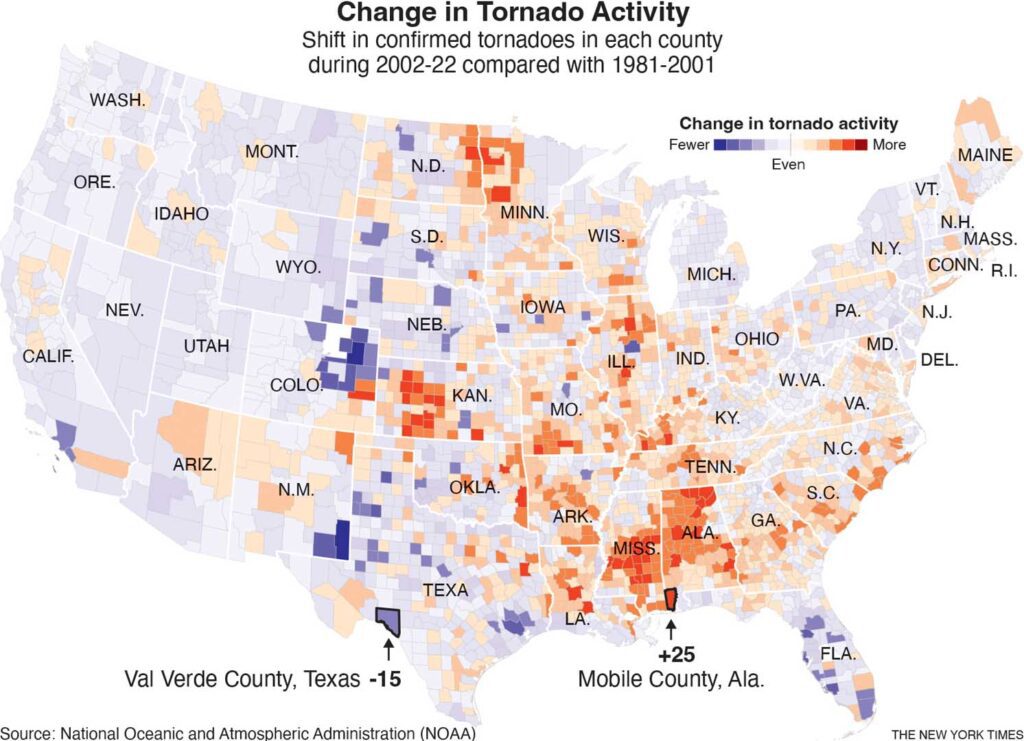

Tornado detection systems have improved, especially since the 1990s, allowing scientists to count tornadoes that might have gone undetected in previous years, said John Allen, a climate scientist focused on historic climatology and risk analysis at Michigan State University.

That plays a role in the historical trend showing more tornadoes in recent decades.

While this year’s worst storms were concentrated in the Midwest, many counties across the South have seen an increase in tornado activity in the past 20 years, compared with the prior two decades. The same counties’ demographic conditions, including low incomes and large mobile home populations, make them especially vulnerable to major disasters.

“It only takes an EF1 to do significant damage to a home, an EF2 would throw it all over the place,” Allen said.

Prof. Tyler Fricker, who researches tornadoes at the University of Louisiana, Monroe, said we will inevitably see more losses in the region.

“When you combine more intense tornadoes on average with more vulnerable people on average, you get these high levels of impact — casualties or property loss,” Fricker said.

“If you have enough money, you can protect yourself,” he added. “You can build out safe rooms. You can do things. That’s not the case for the average person in the Mid-South and Southeast.”

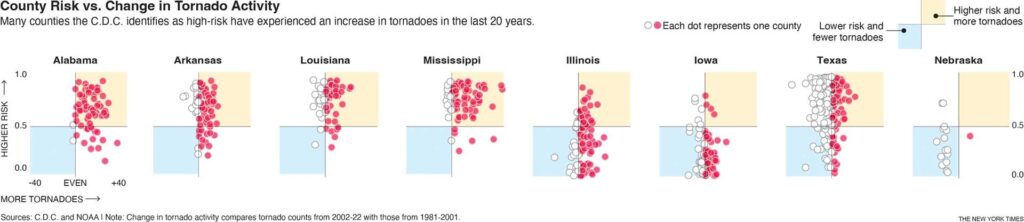

The CDC identifies communities in need of support before, during and after natural disasters through a measure called social vulnerability that is based on indicators such as poverty, overcrowding and unemployment.

Most counties in Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana and Mississippi are both at high risk by this measure and have experienced an increase in tornadoes in the last 20 years, relative to the 1980s and 1990s.

In the states with the most tornadoes this year, most counties have better prepared infrastructure for these kinds of events.

Stephen Strader of Villanova University, who has published an analysis of the social vulnerabilities in the Mid-South region and their relationship to environmental disasters, said the most vulnerable populations may face a tough year ahead.

While two major hurricanes had the biggest impact on the region this year, La Nina will influence weather patterns in 2025 in ways that could cause more tornadoes specifically in the vulnerable areas in the South.

Although not completely definitive, NOAA studies suggest that EF2 tornadoes, which are strong enough to blow away roofs, are more likely to occur in the southeastern United States in La Nina years.

“Unfortunately, a La Nina favors bigger outbreaks in the southeast U.S.,” Strader said. “So this time next year we might be telling a different story.”

Sources and Methodology

Damage costs estimates of tornado-involved storms as reported by NOAA as of Nov. 22.

Historical tornado records range from 1950 to 2023 and include all EF category tornadoes as reported by NOAA.

The Social Vulnerability index is based on 15 variables from the U.S. census and is available from the CDC.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.